by flynn j. ell

by flynn j. ellMatters little if an ancient Indian spiritual leader squatted at the entrance with his hand drum and chanted a plea for healing from the Creator.

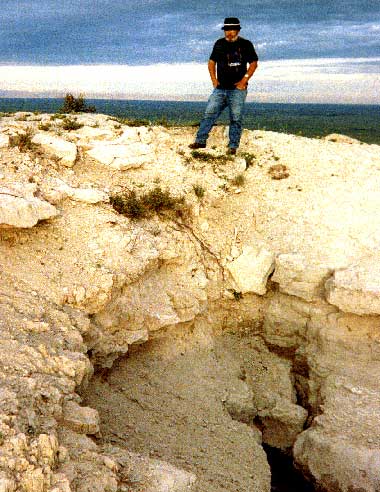

Or a young modern visitor skipped around edges of the dark hole in the white limestone to warnings from a parent to "be careful."

The mystery was there and most likely will always be there, beckoning for further exploration and unraveling.

In our early recent history, the Medicine Hole still breathed cool air in summer and hissed vapor in winter, leading some to theorize it was used by Native Americans as a healing center.

Concerned settlers have dynamited the cave shut for safety on occasion,then reopened the orifice to explore its innards.

We've come to know the area as Tachawakute, the Sioux word "for place where they kill the deer."

But a Mandan Indian merely smiled at that and replied that his people called the area, Baheesh, for the "Mountain that Sings."

To the west of the Medicine Hole stands Signal Rock, said to be used by Indians as a signaling point. Others say there are ceremonial thrones to the west.

The hole, however, was and continues to be the center of attention.

The Federal Writers Project reported in 1938 that Native American tradition divined that the first buffalo had emerged upon earth from the Medicine Hole.

"Today the hole is little more than an elongated three-foot-deep depression in the flat limestone surface of the mountain top," was the report then.

It had been explored to a depth of 80 feet before it was closed, but extreme cold below that depth made further descent difficult.

Among Medicine Hole legends is a belief by some that 5,000 Sioux fleeing from the onslaught of Gen. Alfred Sully's cannon attack on their village used the cave to escape to the Badlands.

Both Sioux and Mandan warriors may have used the hole to escape from their enemies, in the former's case soldiers, in the latter case, a Sioux war party, according to a piece of Mandan oral history.

Another legend is that giants once dwelt in the hole and swept down upon visiting tribes to steal their women and disappear again into the mountain.

Modern realists have discounted much of this while never actually exploring the depth of the cave to its outer limits.

Among modern explorers was Earle Dodd, who on July 2-3 in 1972, led a party which spent about 14 hours in the cave.

Dodd, an automotive shop instructor at UND-Williston Center, thought one passage led to a rock slide area on the west side of the mountain.

Dodd was accompanied by his wife and son and fellow UND instructor Oliver Huset and his son.

After reopening the cave, they reported that it had three passageways. One after an initial drop of 20 feet, extended westerly for 120 feet.

Using lanterns, they cleared the passage of fallen rock and extended it to within ten feet of what they believed was its outlet.

Another passage, 30 feet higher and parallel to the one cleared was too narrow to explore.

And a third passageway, after dropping 20 feet, was said to continue down 120 feet in an easterly direction.

The same article by Leonard Lund of the Minot Daily News reported the first known white man to go into the cave was early Killdeer settler Simon Cuskelly who dropped into the hole in 1910 with a rope around his waist.He descended until his lamp went out.

Subsequent explorations were blocked by plugged passageways so that to this day no one has successfully explored the mysterious regions of the Medicine Hole.

This one fact alone keeps the Medicine Hole on one's mind after a visit. Who will be the first to ever fully explore the underground corridors?

It is also known that among the tribes, the Killdeer Mountains are a sacred site but only recently have Native Americans begun to return to it.

Sioux descendants came back for ceremonies in 1998 and 1999 to honor their ancestors who were killed in the Battle of Killdeer Mountains on July 28, 1864.

The first year the Sioux performed the Releasing the Souls ceremony and the second year, Wiping the Tears Away ceremony.

The Medicine Hole lies atop the South Mountain of the Killdeers eight miles northwest of the city of Killdeer. A trail leads from a campground to the top which is 3,140 feet above sea level and can be climbed in less than an hour.